Cover Photo: Shanghai, China, April 1910, A Purim party.

Credit: Yad Vashem

A formidable though short-lived Sephardi presence in early 20th-century Shanghai fostered unique interpretations of Jewish texts and perceptions. The community may have disappeared, but the ideas live on.

Both in Israel and abroad Jews are lining up according to a conventional divide: the conservative and religious nationalists on one side, universalist secularists on the other. Yet at the turn of the twentieth century in late-Ottoman Jerusalem, a third, integral path was visible, a Sephardic tradition that was religious, Zionist, and universalistic. Deeply rooted in Jewish law, poetry and theology, the Sephardic Judaism of old Jerusalem was fluent in kabbalistic texts and free in its interpretation and use of those texts. It was not, however, ‘modern orthodoxy,’ because it understood itself to be an organic continuation of a venerable Jewish tradition with Spanish bona fides. Called by its present-day practitioners ‘classic’ in order to distinguish it from later developments among Sephardic thinkers and communities, the Classic Sephardic tradition combines deep Jewish learning with a celebration of human excellence, and for a short period, it occupied center stage in Jazz Age Shanghai.

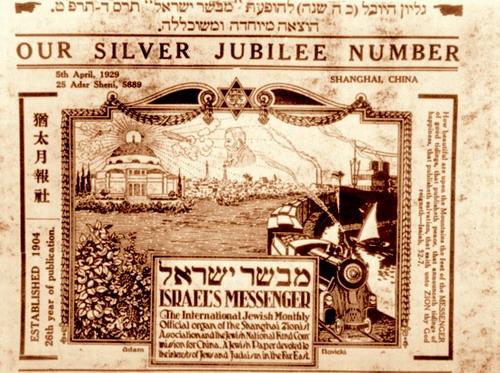

Classic Sephardic Judaism found a home in Shanghai during the first half of the twentieth century thanks to the efforts and support of the Baghdadi Jewish community. Free to pursue their business, political and spiritual interests in Shanghai’s British-run ‘International Settlement,’ the Baghdadi Jewish community of Shanghai published local news and big ideas in Israel’s Messenger (IM), an English-language newspaper that was edited for many years by N.E.B. Ezra, a religious Jew and energetic Zionist from a well-known and well-connected Baghdadi Jewish family. Baghdadi Jewry varied in its commitments to Zionism, but Shanghai’s Baghdadi Jewish community established the Shanghai Zionist Association in 1903, ten years before the first Zionist organization was set up in Iraq. IM was then established in 1904, and under Ezra’s editorship, the newspaper’s masthead declared itself to be “A fearless exponent of traditional Judaism and Jewish Nationalism.” IM accordingly included discussions of local Jewish concerns together with long-form essays that probed the depths of Judaism and the progress of the Zionist movement.

Israel’s Messenger – Silver jubilee issue, 5 April 1929 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

IM’s horizon, however, was not limited to the Jewish world. Ezra advocated for Zionism in an Asian context, and he published entries on the Zionist movement by Japanese, Chinese, and Hindu intellectuals and public figures. The feather in IM’s cap was a letter in support of Zionism from the founder of modern Chinese nationalism, Sun Yat Sen, who wrote “to assure you of my sympathy for this movement which is one of the greatest movements of the present time.”

IM’s openness and receptivity to other cultures, religions, and peoples transcended purely diplomatic concerns. Together with local and general Jewish items, the Shanghai Jewish newspaper gave a platform to the Sanskrit scholar and historian of Bengali literature, H.P. Shastri, to offer his Hindu perspectives on Israel’s role in the revival of Asia, and to Lahore-based Muslim author Muhammad Manzur Illahi to offer an Ahmadiyyan view of Jewish-Muslim relations. IM also published essays on Christianity and theosophy and incorporated features on international figures like Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali Nobel prize-winning poet whose 1924 visit to Shanghai’s “Marble Hall” was extensively covered in the newspaper. Both Tagore’s visit itself and its coverage in IM illustrate the deeply rooted Judaism, spirited Zionism and spiritual openness that characterize the Classic Sephardic tradition.

Constructed in 1924 and modeled after the palace in Versailles where the Allies convened to conclude WWI, Marble Hall was built by a leading Baghdadi-Jewish businessman, Eli Kadoorie. The palatial new home featured a block-long veranda and sixty-five-foot-high ceilings crowned by 3,600 electric lights, and it quickly became one of the most famous addresses in the International Settlement. It’s also where Kadoorie hosted Tagore and his team when they visited Shanghai in 1924. Kadoorie was not an intellectual, but he supported the Classic Sephardic tradition and saw its flourishing as a way to glorify his community. So, he invited guests from across the city to a banquet in honor of the famous Bengali “Poet of Asia,” opened with “a few well-chosen words” welcoming Tagore and then called upon Rabbi Dr. Ariel Bension (1880-1932), the Zionist emissary and renaissance man who was living in Kadoorie’s Shanghai mansion, to deliver the opening address.

It’s worthwhile lingering over Benison, because his individualistic blend of traditional, Zionist and cosmopolitan elements embodied the Classic Sephardic Judaism that was cultivated in pre-State Jerusalem and that thanks to Kadoorie and N.E.B. Ezra found a home in Shanghai.

Ariel Bension was born in 1880 to a Sephardic Jerusalem family. His father was a kabbalist, in Bension’s words, “a descendant of a family of Spanish exiles settled in Fez” who lived “a life of beauty, of sanctity, of melody, of silence” at the famed Beit El kabbalistic seminary in Jerusalem’s Old City. Young Ariel learned at Tiferet Yerushalayim, the nineteenth-century Sephardic Yeshiva that taught languages, history and sciences together with sacred subjects, then studied at Swiss and German universities before earning a doctorate at the University of Bern. In 1910, Bension returned home to Ottoman Jerusalem to work as a teacher and newspaper reporter. By now a polyglot and Hebrew-language poet and writer, he set out again in 1913 to serve as Chief Rabbi in Monastir, Macedonia, the same year that he attended the 11th Zionist Congress in Vienna, where he organized a special committee of Sephardic delegates.

Bension was being hosted in Kadoorie’s new palatial residence and regularly featured in the pages of IM because he had begun another chapter in his adventurous life, this time as a Zionist representative for the United Israel Appeal serving Sephardic Jewish communities in South America, the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa, Egypt, Iraq, southeast Asia and Shanghai. Bension carved out a dual role for himself as an educator and (very successful) fundraiser, motivating Sephardic Jews to support the Zionist movement while articulating a vision of Zionism as the Jewish people’s symbolic and literal return to the East. He circulated his vision in poetry and prose and in 1931, a year before his premature passing, published The Zohar in Muslim and Christian Spain, a literary-mystical-historical study that celebrated the Zohar’s “spirit of fantastic adventurousness with which all currents of Spanish life were impregnated,” including the spiritual adventures of Spanish Christians and Muslims like Ramon Lulle, Ibn Arabi, and Cervantes. As for the book’s view of the Zohar, Bension believed that its ideas are ancient, but that the Talmudic sage Shimon bar Yochai did not write the book. Instead, the Zohar’s hidden mystical Sephardic author hung his capiello on Shimon bar Yochai because:

“Inspired by the belief that his revelations came from the Source of Divine Inspiration, that they emanated the very Source of Truth, the author sought to lift his work to a higher plane. He therefore chose some high personality, preferably one who had been a source of inspiration to himself, or the guiding spirit of his own life, and made him responsible for proclaiming this new truth to mankind.”

Bension, it should be noted, also believed that the Zohar’s “spirit of fantastic adventurousness… is beginning to disappear and threatens to sink into complete oblivion,” and he wrote his book as “nourishment for the soul and… food for thought” in order to keep the Sephardic “living creativeness” alive. While The Zohar in Muslim and Christian Spain was largely ignored both in religious and academic communities, the book shines when read in light of the “fantastic adventurousness” of Bension’s own life.

During the meeting with Tagore, Bension began his address at Kadoori’s Marble Hall by honoring him as “the light of Asia.” Surrendering to the poet’s mystical vision, Bension said that to read Tagore “is to have the universe transformed in one’s eyes into the temple of God… who is to be found everywhere and in everything.”

But Bension was not just reading Tagore. He was, in his words, reading Tagore in translation, “from Bengali to Hebrew, that is, from one oriental language to another.” Bension, a champion of the revival of the Hebrew language, recalled how:

“One moonlight night while walking on the hills of Jerusalem a great Hebrew writer said to me, “I wonder if you have realized how near Tagore’s poetry is to ours and how justified is his call to return to the mentality as expressed by our prophets of old… Is not the poetry of Bialik and the theory of Ahad Ha’Am a call to the young generation of Israel to return to the spirit of All, and is this not the aim of Zionism?””

Bialik and Ahad Ha’Am were leaders of the Hebrew cultural revival during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Bension’s linking of spiritual-literary discussions in the hills of Jerusalem to Tagore’s Bengali poetry in Hebrew translation at a Shanghai event illustrates the unique form of Judaism – deeply rooted in Jewish tradition while also at home in the best of human culture − that was offered a physical and journalistic platform in the dynamic Chinese port city.

Tagore the Nobel-prize winning poet followed Bension’s opening address by accentuating the Asian context:

“You welcome me as the poet of Asia and I am proud of it. I have deep sympathy for that great movement of yours in the West of Asia in the creative activities of Zionism… for it represents a great truth – the marvelous stir of awakened life to discover its own home land. Yes, the whole mind of Asia is hungering for its spiritual home.”

Further accentuating the Asian dimension of the Jewish national revival, Tagore continued:

“For several centuries Asia has not sent any great voice to deliver any great message… Now, the time has come for Asia to speak again… My appeal to you my brethren as an Asiatic poet is for the winning of the freedom of the soul… May Asia send forth again her great ideals… Let Asia offer her prayers – arising from the depth of her humble suffering soul – her prayer to win humanity back.”

Ezra followed Bension and Tagore’s impassioned addresses with his own “Notes and Reflections” in which he returned to Zionism’s Asian context – “The future of our people is indissolubly bound up with Asia” – and praised Tagore as “the apostle of Asia… He carries with him all that is best and noble with which to ennoble and beautify the ideals of the Asiatic race. We glory in him.”

For Ezra this glory wasn’t purely aesthetic, it was also deeply spiritual and connected to traditional Judaism. “We realize that he is a great benefactor of the human race, a teacher… Our ancient sages gloried in the role that teachers had played.” At which point Ezra quoted three Talmudic texts on the honor befitting teachers. That Tagore wasn’t Jewish was irrelevant, as it is for lovers of the poet’s soulful mystical voice.

Tagore’s visit to Shanghai clearly illustrates the Classic Sephardic form of Judaism celebrated in Shanghai, but it was far from alone. IM also celebrated Jewish figures whose writings and activities reflected the Classic Sephardic approach. The rabbi most often featured in the pages of IM was Rabbi Bension Meir Hai Uziel (1880-1953), an old friend and learning partner of Bension also born in 1880 who attended the same Yeshiva, Tiferet Yerushalayim, and who grew up to become the Chief Sephardi rabbi of Tel Aviv and later the first Sephardic Chief Rabbi of the State of Israel. Like Bension, Uziel’s vision was religious, Zionist and receptive to the best that humanity has to offer. Also like Bension, Uziel was fluent in kabbalistic literature and remarkably free in how he used it. Although he opens his two-volume work of Jewish thought, Hegyonei Uziel, by professing to be innocent of kabbalistic learning, Uziel freely suffuses the entire work with kabbalistic terms, ideas and texts that he uses as material in articulating his unique spiritual vision. Uziel’s sermons for the Jewish holidays and letters to the editor were published in IM, as well as some brief interviews, and in one letter to the editor, he even asks that his personal regards be conveyed to his friend, Ariel Bension.

By featuring and celebrating Uziel and Benison in his newspaper, Ezra was both honoring and offering a home to the Classic Sephardi Judaism of old Jerusalem. In a sense, in the pages of IM, Shanghai became a chapter in an old Sephardi Jerusalem tale. But if Classic Sephardi Judaism’s moment under the Far Eastern sun is a chapter in a larger story, the continuation of the narrative thread is harder to find.

Ezra passed away in 1936, and in 1937 the Japanese occupied Shanghai. Israel’s Messenger ceased publication in 1941. By the time the Chinese Communist forces conquered and united the mainland in 1949, the Jewish community of Shanghai was, as they say, history.

Rabbi Uziel lived to compose the prayer for the State of Israel together with R’ Yitzhak Herzog (and S.Y. Agnon’s edits), but he passed away in 1953. His writings and teachings have largely gone ignored by religious communities in Israel and abroad. Further, during the first half of the twentieth century the more limited scholarly horizons of Yeshivat Porat Yosef displaced Tiferet Yerushalayim as the center of traditional Sephardi scholarship in Jerusalem.

In relation to Bension, scholars of Kabballah, Israeli history and literature and even Islamic spirituality have written a few articles about him, but Benison has been for the most part ignored within the academy. Jonathan Meir critiques Bension’s portrait of kabbalistic decline in Jerusalem, but he ignores The Zohar in Moslem and Christian Spain and, as such, doesn’t investigate the book as an example of enduring kabbalistic creativity. Almog Behar and Yuval Evry explore Bension’s meeting with Tagore, but they completely abstract the meeting from its specifically Baghdadi-Shanghai context. In Orthodox circles, Bension is completely unknown in Israel and abroad, and while Routledge is still publishing The Zohar in Moslem and Christian Spain, it’s available under the category of “Muslim Spain.”

In sum, what happened to Classic Sephardic Judaism and why hasn’t the Classic Sephardic Judaism of Shanghai with its origins in Jerusalem and the Sephardic diaspora not been seriously studied by scholars? And why haven’t the works of Classic Sephardic Judaism been taken up in centers of Jewish Studies? The answers to these questions themselves require a full-length study, far beyond the limitations of the present essay. Factors connected to the tectonic shifts in twentieth-century geo-politics, Jewish migrations during the same period, the ethnic roots of American Jewry, the development Israeli society and the character of the academy and modern orthodox yeshivot are involved. At this point, however, two broad points deserve mention relating to the two postwar centers of Jewish life.

First, the integral vision championed in the pages of IM and in the writings of Uziel and Bension did not fit into the strict socio-cultural divisions that ultimately emerged in Israeli society. Likewise, in the United States, almost all of the active centers of Jewish life are distinctly Ashkenazi in their historical and ideological orientation, so Rabbi Uziel and Ariel Bension are not even on their radar. What’s more, the Classic Sephardic Tradition hasn’t been a serious object of academic study both in Israel and the United States because the academy has largely followed the general societal trends. And while Classic Sephardic Judaism has continued to develop in France to some degree, though impacted as in Israel by Ashkenazi influence, the ties between France and these two other centers have been more tenuous.

That said, it’s important to note that Classic Sephardic Judaism has not completely disappeared. It animated the work of Rabbi Yosef Messas (1892-1974) and Rabbi Yehuda Ashkenazi (aka Manitou; 1922-1996), North African-born and broad-minded, sophisticated scholars who settled in Israel and whose writings combined traditional Judaism, passionate Zionism and universalist sensibilities. In France, Shmuel Trigano’s independent review of Jewish Studies, Pardѐs, showcases authors who explore the classic Sephardic perspective, and in Israel, Ophir Toubul’s “Golden Chain” and Rabbi Yitzhak Shouraqi’s scholarly and educational work aim to revitalize this tradition. In America, scholars and leaders such as Rabbi Marc Angel and Rabbi Daniel Bouskila head The Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals and the Sephardic Educational Center, organizations outside of the academy that are animated by the same nourishing blend. In this context, Professor Daniel Elazar (1934-1999), deserves special mention. A prominent professor of political science, the first president of the American Sephardi Federation (ASF), founder of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and author of the monumental four-volume Covenant Tradition in Politics (and much more), Elazar was a princely embodiment of the Classic Sephardic tradition. He delineated his vision of Sephardic Judaism’s mission in an extended 1992 essay, “Can Sephardic Judaism be Reconstructed?” in which he called for the revival of the “seriously Jewish, yet worldly and cosmopolitan” Classic Sephardic Judaism. Elazar’s vision remains the ASF’s organizational modus operandi.

As for Classic Sephardic Judaism’s platform in Jazz Age Shanghai, the Jewish world and its scholarly circles share the assumption that China has never been home to any kind of substantive Jewish culture. The breakthrough occurred, perhaps predictably, thanks to efforts from outside of the university setting. Interestingly, pro-Zionist Chinese sensibilities provided the initial information that led to the much larger story.

In 2022, Professor Xiao Xian from Yunnan University shared Sun Yat Sen’s letter in support of Zionism with a group of Israeli colleagues at a faculty seminar organized by SIGNAL, an independent think tank and academic organization based in Israel focusing on China-Israel relations. Sun still occupies an important place in the Chinese political imagination, and it is through the discovery of Sen’s letter in IM and SIGNAL’s active encouragement of additional research that Israel’s Messenger’s role as a patron of Sephardic Jewish culture in China emerged. In more ways than one, it seems that the new mental frameworks capable of comprehending the breadth and depth of Jewish life in the twenty-first century will come from surprising places.

As the Jewish people increasingly splits today along secular cosmopolitan and conservative/religious nationalist lines, it’s important to remember that N.E.B. Ezra, Rabbi Dr. Ariel Bension and Rabbi Ben Zion Meir Hai Uziel participated in a shared adventure that embraced spiritual vitality wherever it’s found.

Seriously Jewish yet highly receptive, the Classic Sephardic Judaism onstage in Shanghai and in the pages of Israel’s Messenger waits to be recovered by all those who want Judaism to stand on its own two feet and freely engage in cultural exchange with the best of human civilization. The fit would seem to be natural. After all, Jewish texts teach that there are seventy faces to both the Torah and humanity. Seen from that perspective, a position of strength befitting Israel’s growing material power, the Jewish tradition can freely share its multi-dimensional vision with anyone seeking elevated perspectives on human flourishing during our fractured times.

Dr. Aryeh Tepper is SIGNAL’s Director of Israel Studies in China

Many thanks to The Tel Aviv Review of Books for permission to republish the essay.